Its a Friday night in August 2009 when Zethu Mashika makes a call that changes everything. Its his birthday month and hes about to be given an opportunity that will alter the path of his life. A spontaneous check-in with a friend turns into an invitation: Dont you want to make music for a film?

This is the night that Mashika discovered film scoring. He had happened to find his friend in the middle of an emergency, struggling to make the music for a grad film he was working on.

They came to pick me up and I scored [the film], he says. Thats when I caught the bug, got infected, and then, you know, the rest is history.

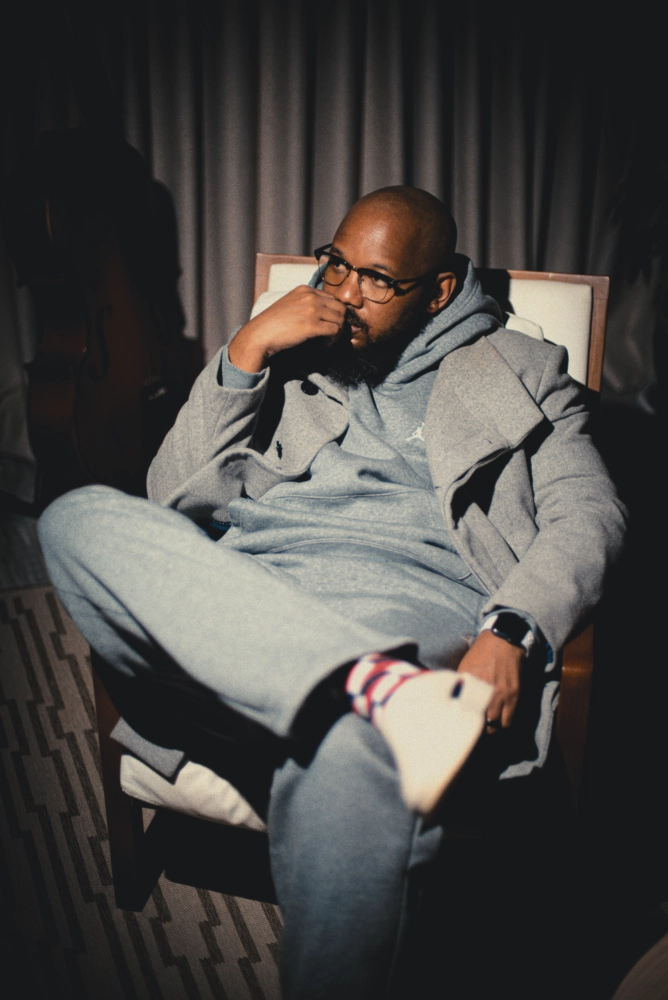

Mashika, born and raised in Benoni, Gauteng, had been working as an artist and producer, a career that began in 2003 during the surge of hip-hop and kwaito.

I was the artist, producer type. I got to produce some tracks on Flabbas album. At that time the Zulu Mob and H2O were the big guys. And then I did a track with RJ Benjamin.

During his years as a producer, he explored different genres of music, including rock and Chinese, to figure out which lane he would thrive in.

Among his experiments was film music, which didnt make much sense to him at first.

When I listen back, it sounds horrible.

But something in it stuck.

I didnt realise it would build the life I wanted, or make me the person I wanted to be. Youre not sure until you actually do it.

After that first short film, everything changed.

It was 12 minutes long, and I scored the whole thing in one night. I wouldnt do that today, he laughs. But when I came back, I was no longer a producer. I was a composer.

After discovering his passion for film composition, Mashika shifted his focus from producing music to creating scores that enhance visual storytelling.

Mashika rebranded himself overnight. He started downloading trailers, stripping them of sound and scoring them for practice. He then used those as pitch material. Thats how I got my first film.

Meaning: The score for Go (left) is Zethu Mashikas sons going-to-school music. He worked with Forest Whitaker and Eric Bana (right) on The Forgiven. Photos: Netflix & Light and Dark Films

Meaning: The score for Go (left) is Zethu Mashikas sons going-to-school music. He worked with Forest Whitaker and Eric Bana (right) on The Forgiven. Photos: Netflix & Light and Dark Films The experience of scoring the grad film ignited a newfound dedication within him, one that would lead to him having a successful career in the industry as a film composer.

He landed his first professional project, Zama Zama. While still working on it, another opportunity landed: SKYF, starring Thapelo Mokoena. Although Zama Zama came first, SKYF was his first fully completed feature. A South African Film and Television Awards nomination followed soon after.

It was a stamp. Like, Yes. This is it, he said.

The projects kept rolling. One of Mashikas most significant was the 2017 feature The Forgiven, starring Forest Whitaker and Eric Bana.

That was a big one. A proper learning curve. You see how the machine moves on that level: how an editor works, how a director with depth directs.

Working with directors who bring vision and emotional depth reshaped how Mashika thought about music in film.

Theres a difference between curating pretty shots and telling a story. Same with music. Some just do background music. Others push you to go deeper. When you work with someone like that, youre not just making sounds, youre putting in layers.

He likens it to becoming an active watcher involved in every frame and every line of dialogue. That changes how you compose.

The creative process for a score looks different for every composer. Mashikas requires a helping hand from digital tools.

Every time I start a film, Im like: I dont know if I can do this. Only 12 notes! You have to find a combination no ones done that still fits the picture, the psychology, the world.

Unlike many composers, Mashika doesnt play instruments. No muscle memory. I hear everything in my head, and I input the notes with a mouse, one by one.

That limitation is a strength. Its slow, but its intimate. I know why every note is there, why every gap matters. Some just go with sounds good. But I know why Im putting icy strings down low, or that brass over there. Its painting a picture.

Hes also keeping up with new tech, tools that let him hum melodies into a mic, which then generate MIDI data. Its weird. But its fun.

Mashikas sound is distinct: a mix of brass, strings, alternative synths and voice. Each has its emotional use. Brass can fill a space like nothing else. Its triumphant, but you can make it sound so sad. Strings can go dark. Synths, especially the weird ones, blur the line between music and sound design.

His inspirations include giants such as Hans Zimmer, J�hann J�hannsson and Ludwig G�ransson, but Mashikas approach is personal. He describes himself as a spiritual composer, for whom work and life are one and the same.

There are people who have a job and then a life. For me, theyre the same. I shoot my wifes commercials for fun. I help with her photo shoots. I like being on set. Its all the same energy.

That energy has spilled into fatherhood. On car rides to school, his four-year-old son insists on listening to tracks from Go, a recent Netflix project Mashika scored. Thats now our school music. He sings along. Its the best thing.

At this point in his life, Mashika says theres nowhere else hed rather be.

When you see how your music affects a film, how empty it is without it, you know youre exactly where you need to be.