Changing attitudes before Brailles birth helped pave the way for tolerance. Philosopher Denis Diderots 1749 Letter on the Blind argued blind people have the same intellectual capacity as sighted people. Schools for the blind opened in France and England in the late 1700s, but Brailles writing system provided a mean...

Changing attitudes before Brailles birth helped pave the way for tolerance. Philosopher Denis Diderots 1749 Letter on the Blind argued blind people have the same intellectual capacity as sighted people. Schools for the blind opened in France and England in the late 1700s, but Brailles writing system provided a mean...

Where would we be without writing? From its origins over 5,000 years ago in ancient Mesopotamia, the history of writing echoes the history of humanity. The Greeks and Romans developed unique alphabets, the Chinese evolved complex characters, and today we read novels, newspapers, and social media. A bedrock of human civilization, writing is fundamental for the rule of law and the accumulation of knowledge and culture. Yet it was not until the 19th century that blind people had access to writing.

Between 1824 and 1825, Louis Braille created a system of raised dot letters that could be read with the hands. Initially ignored, his invention would be universally adopted by the 20th century, opening a new world of learning for the visually impaired. In a speech at the Sorbonne on the centennial of Brailles death, Helen Keller said, We, the blind, are as indebted to Louis Braille as mankind is to Gutenberg.

( How to make travel more accessible to the blind. )

The youngest of four children, Braille was born in 1809 in the village of Coupvray, 22 miles east of Paris. His father, Simon-Ren�, worked as a saddler, a trade that was always in demand. The family lived comfortably, also cultivating vines for winemaking. Luxuries, such as a bread oven, can be seen today in the house, transformed into the Louis Braille Museum in the 1950s. The centerpiece exhibit is the re-created leather workshop where Braille suffered the accident that would lead to his loss of sight, changing his destinyand the course of history.

As a curious three-year-old, Braille snuck into the shop when no one was around and played with the tools he often watched his father use. When he tried to punch a hole in the leather with an awl, the tool slipped and pierced his eye. This horrific injury led to an infection that spread to both eyes, leaving him blind by the age of five, as antibiotics were not yet discovered.

Braille was born in Coupvray, east of Paris, in Frances Brie region, famous for the cheese of the same name. His childhood home, which became the Mus�e Louis Braille in the 1950s, is a traditional three-story house built the 1700s. The family worked as saddlers in Coupvray for more than a century, passing on the profession. In the museum, the leather workshop, shown here, showcases an original table, horse bridles, and an awl of the type that blinded Braille in the horrific childhood incident. A marble plaque outside the house honors the inventor with these words: He opened the doors of knowledge to all those who cannot see.

Braille was born in Coupvray, east of Paris, in Frances Brie region, famous for the cheese of the same name. His childhood home, which became the Mus�e Louis Braille in the 1950s, is a traditional three-story house built the 1700s. The family worked as saddlers in Coupvray for more than a century, passing on the profession. In the museum, the leather workshop, shown here, showcases an original table, horse bridles, and an awl of the type that blinded Braille in the horrific childhood incident. A marble plaque outside the house honors the inventor with these words: He opened the doors of knowledge to all those who cannot see. His distraught parents did not want their sons fate sealed in an era when the visually impaired were treated as subhuman, often ridiculed for their disability. On French city streets, blind people were paraded in silly outfits or resigned to begging. Public school education was not yet mandatory in France, but Brailles parents understood the importance of literacy. To aid his son, Simon-Ren� hammered nails into the shape of the alphabets letters on panels, and a priest named Abb� Jacques Palluy began to instruct Braille.

By the age of seven, he attended the local school, where he was the only blind student. His teacher was struck by his raw intelligence and happy demeanortraits that were admired by Brailles friends over the course of his life. A few years later, a scholarship was secured for him to continue his studies at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth, the worlds first such school and one thats still in existence, now called the National Institute for Blind Youth, or INJA. At 10 years old, he would be its youngest ever student.

Most astonishing of all was his close-knit familys consent in allowing him to leave home. His mother and father couldve just as easily kept him in the village, explained Farida Sa�di-Hamid, the curator of the Louis Braille Museum. They are going to write his destiny without knowing it. This familial support would prove a constant for Braille, and he would continue to return to Coupvray to rest and recharge throughout his life.

( These scientists set out to end blindness. )

This specially adapted dominoes set was owned by Braille. At seven years old, he was the only blind student at the local school.

This specially adapted dominoes set was owned by Braille. At seven years old, he was the only blind student at the local school. A chance for education

Founded by pioneering educator Valentin Ha�y, the institute was groundbreaking in its methodology and approach. The students learned a variety of academic subjects and a manual trade. Ha�y had devised a means of embossing books with raised letters, which the children could read with their fingertips, albeit with great difficulty. The school would bring Brailles salvation and his demise, because its likely where he caught the tuberculosis that would kill him.

The building, situated in the longtime student hub of Pariss Latin Quarter, was filthy, damp, and run-down. It had even served as a prison during the French Revolution. But despite the noxious conditions, and the sometimes severe punishment doled out for rule-breaking kids, Braille thrived, making friends and excelling at his studies. Teachers noted his remarkable smarts and spiritual quality. His friend Hippolyte Coltat would later write, Friendship with him was a conscientious duty as well as a tender sentiment. He would have sacrificed everything for it, his time, his health, his possessions.

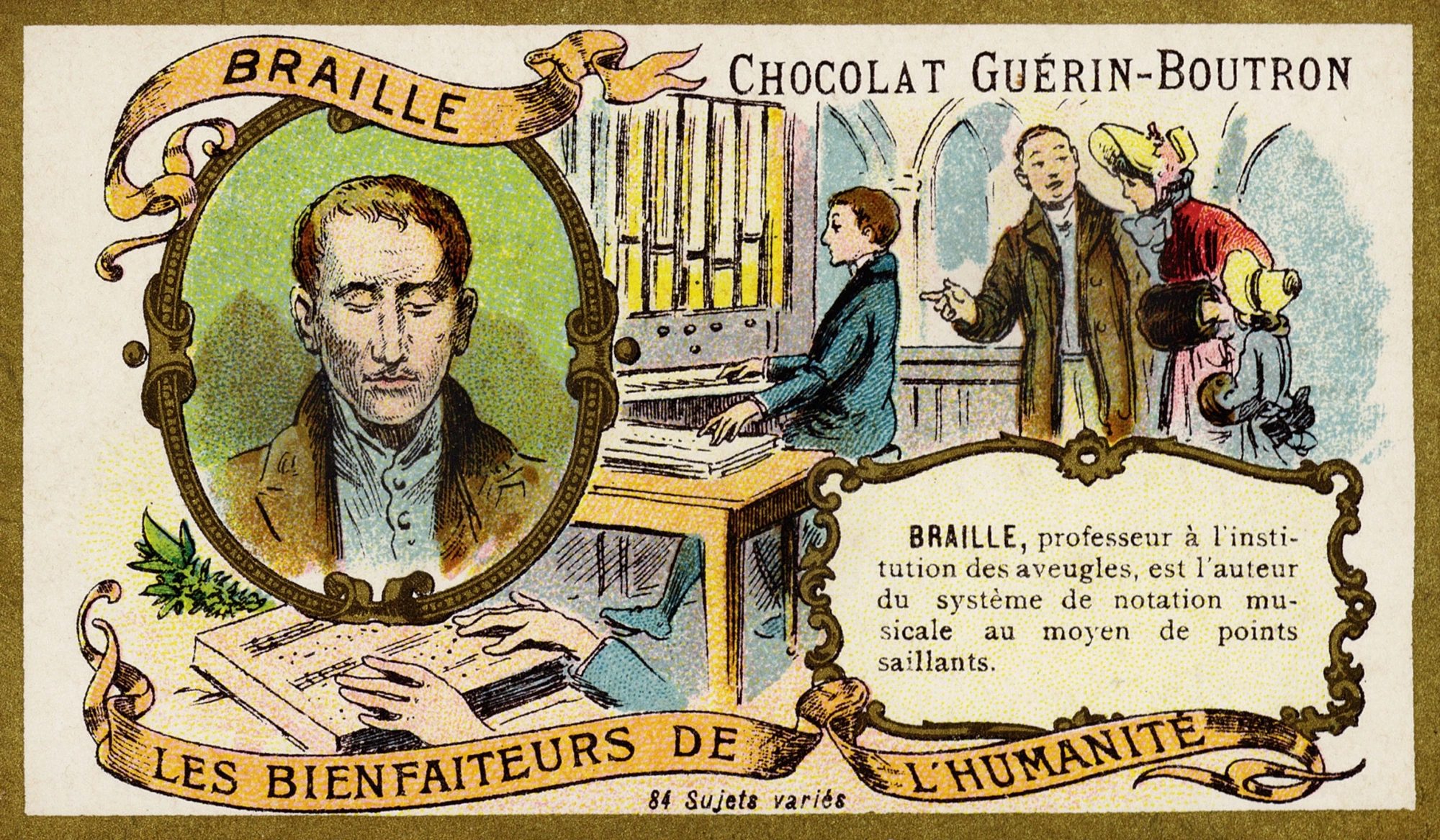

An ear for music Braille's passion for music was born at the institute, where professional musicians gave classes and students, shown playing in a 1903 illustration, could join the orchestra. He won the cello prize in his fifth year, develop...

An ear for music Braille's passion for music was born at the institute, where professional musicians gave classes and students, shown playing in a 1903 illustration, could join the orchestra. He won the cello prize in his fifth year, develop... The catalyst for Brailles invention came in 1821. Capt. Charles Barbier, an artillery officer, had devised a means of night writing for the French Army to transmit and carry out orders under the cover of darkness. Convinced of its merit for blind people, Barbier transformed this dot-and-dash code into a phonetics-based system he presented to the students. There were linguistic flawssonography reduced language to sounds, so spelling was inaccurate and punctuation nonexistentbut Braille had an epiphany. A dot system could provide an easy and efficient method for the visually impaired to read and write.

An early 1900s chocolate card shows Braille at the organ

An early 1900s chocolate card shows Braille at the organ He spent the next four years working to devise such a code. At the institute, hed pull all-nighters after his classes had finished. Even on vacations home to Coupvray, villagers would describe seeing the boy sitting on a hill with stylus and paper in hand. At the age of 15, he succeeded in creating what would become known as braille writing. The basis was cells of six dots arranged in two columns and three rows. Each combination of raised dots represented a letter of the alphabet. It was elegant in its simplicity and logic.

The schools students quickly embraced its useallowed in an unofficial capacity by Director Fran�ois-Ren� Pignier. Braille humbly acknowledged his indebtedness to Barbier in his 1829 book Method for Writing Words, Music, and Plainsong by Means of Dots for the Use of the Blind: If we have pointed out the advantages of our method over his, we must say in his honor that his method gave us the first idea of our own.

Barbiers code gave Braille (whose statue in Buenos Aires, Argentina is shown here) his big idea: A dot system could enable blind people to read.

Barbiers code gave Braille (whose statue in Buenos Aires, Argentina is shown here) his big idea: A dot system could enable blind people to read. Battle for Braille

Despite Pigniers promotion of braille and letters to the government, the system was not immediately accepted. The established order, dictated by the sighted, was resistant to change and favored the uniform use of one writing system.

Braille became a teacher at the institute at the age of 19. By 26, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, leading to long stretches of convalescence at home in Coupvray. Political machinations at the school led to the ousting of Pignier, whose replacement, Pierre-Armand Dufau, flatly rejected the use of braille. He even burned books and punished students caught using it.

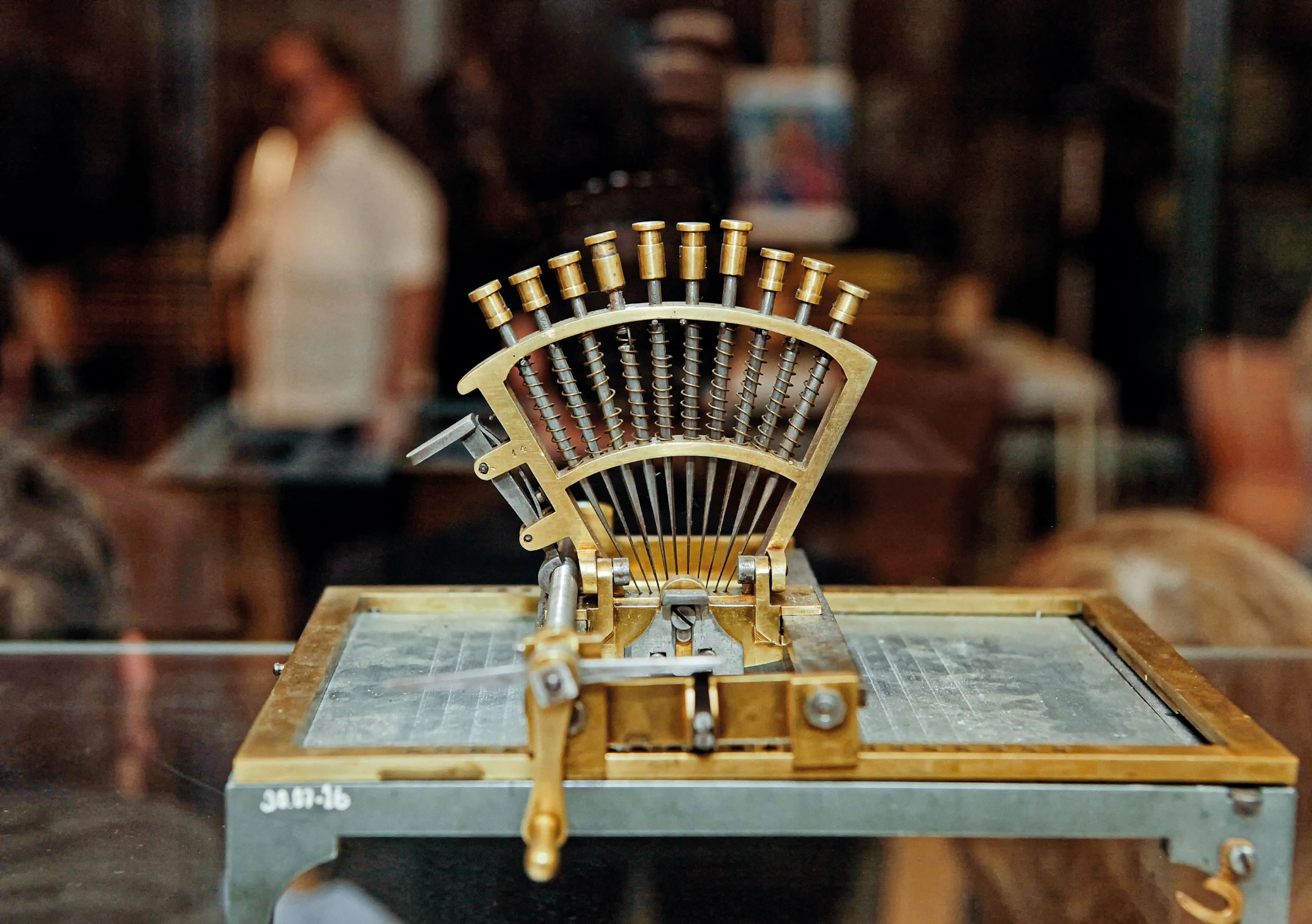

Braille also devised the decapoint system in which raised dots form standard Latin letters. His friend Pierre-Fran�ois-Victor Foucault developed the raphigraphe, shown here, to write decapoint. The system was unwieldy, but Braille used the...

Braille also devised the decapoint system in which raised dots form standard Latin letters. His friend Pierre-Fran�ois-Victor Foucault developed the raphigraphe, shown here, to write decapoint. The system was unwieldy, but Braille used the... Gracefully, Braille persisted in his fight for the acceptance of his new writing system. A letter that he wrote in 1840 to Johann Wilhelm Klein, the founder of a school for blind people in Vienna, shows his humble efforts of persuasion when describing yet another invention, decapoint, a means for blind and sighted people to communicate: I will be happy if my little methods can be useful for your students, and if this specimen is in your eyes the proof of the high consideration with which I have the honor to be, sir, your respectful and very humble servant, Braille.

A 2009 coin from Italy dedicated to Braille

A 2009 coin from Italy dedicated to Braille A moment of recognition finally came in 1844, at the inauguration of the schools new premises on the Boulevard des Invalides. By this time, Dufau had changed his mind about braille, thanks to the insistence of assistant director Joseph Guadet. Following a speech about the raised-dot system, students demonstrated its use by transcribing and reading verse. Guadet later wrote: Braille was modest, too modest ... those around him did not appreciate him ... We were perhaps the first to give him his proper place in the eyes of the public, either in spreading his system more widely in our musical instruction or in making known the full significance of his invention.

Louis Braille did not live to see the universal adoption of braille. He died on January 6, 1852, surrounded by his brother and friends. Not a single newspaper carried a death notice for the man called the apostle of light by Jean Roblin, the first curator of the Louis Braille Museum. Students raised money for Parisian sculptor Fran�ois Jouffroy to create a marble bust based on Brailles death mask.

In 1878 in Paris, a global congress for deaf and blind people proposed an inter- national braille standard. Braille was officially adopted by English speakers in 1932, and postwar UNESCO efforts unified adaptations in India, Africa, and the Middle East. Brailles profound legacy cannot be overstated.

On the centennial of his death, Brailles accomplishments were finally celebrated in a national homage. His body was exhumed from the Coupvray cemetery and transferred to Pariss Panth�on, the resting place of Frances great citizens. (His hands remained in an urn decorated with ceramic flowers at the Coupvray grave.) The parade through the streets of Paris included hundreds of blind people, elbows linked, some wearing dark sunglasses, tapping white canes on the cobblestones.

Braille died of tuberculosis, age 43, in 1852 and was buried in Coupvray. In 1952 his body was reinterred in a tomb in Pariss Panth�on, the mausoleum reserved for Frances greatest figures.

Braille died of tuberculosis, age 43, in 1852 and was buried in Coupvray. In 1952 his body was reinterred in a tomb in Pariss Panth�on, the mausoleum reserved for Frances greatest figures. Yet 200 years after the invention of braille writing, the fight continues. It is a fight to preserve not only the memory of Louis Braille, the subject of surprisingly few biographies, but also the use of his system in the digital age. Increasingly, visually impaired children are learning via screens and audio programs. But neuroscientists argue that writing is essential for thinking, brain connectivity, and learning. The cognitive benefits of writing are fundamentally important. Studies have shown that when a blind person reads braille through touch, the visual cortex is illuminated.

With a shortage of braille teachers worldwide, braille literacy has plummeted, and its very future is in peril. Sa�di-Hamid, the curator of the Louis Braille Museum for nearly 17 years, equates her fight to defend braille as a combat to defend intelligence itself. Noting Brailles extraordinary personality, Sa�di-Hamid said, he always perceived his disability as a strength and not as a limitation. As Braille fought during his lifetime, the fight must go on.

( How the wheelchair opened up the world to millions of people. )

U.S.S.R and India: Alamy; Qatar: Shutterstock Six million people around the world use braille today. Its future is secure in a high-tech world. It can be easily converted to digital formats, and it can be read and written on tactile displays on computers or tablets. An expert braille user can read 200 words a minute (most sighted people can read 250). Although braille literacy is declining, it will be necessary for a future in which an aging population increases the number of blind and visually impaired people. Its strength as a universal system that can be used by anyone, regardless of their linguistic background, has attained international hero status for its French creator. Numerous countries have paid homage to Braille in their postage stamps, including these stamps (clockwise from the left: the U.S.S.R., Qatar, and India). This story appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of National Geographic History magazine.

U.S.S.R and India: Alamy; Qatar: Shutterstock Six million people around the world use braille today. Its future is secure in a high-tech world. It can be easily converted to digital formats, and it can be read and written on tactile displays on computers or tablets. An expert braille user can read 200 words a minute (most sighted people can read 250). Although braille literacy is declining, it will be necessary for a future in which an aging population increases the number of blind and visually impaired people. Its strength as a universal system that can be used by anyone, regardless of their linguistic background, has attained international hero status for its French creator. Numerous countries have paid homage to Braille in their postage stamps, including these stamps (clockwise from the left: the U.S.S.R., Qatar, and India). This story appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of National Geographic History magazine.